Категория / чтения и выступления

Литература и материальность голоса

Подкаст ведет: Татьяна Вайзер.

В гостях: Павел Арсеньев.

19.03.2024, 53 мин.

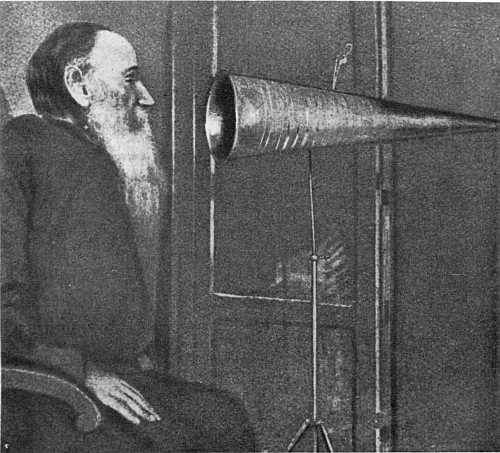

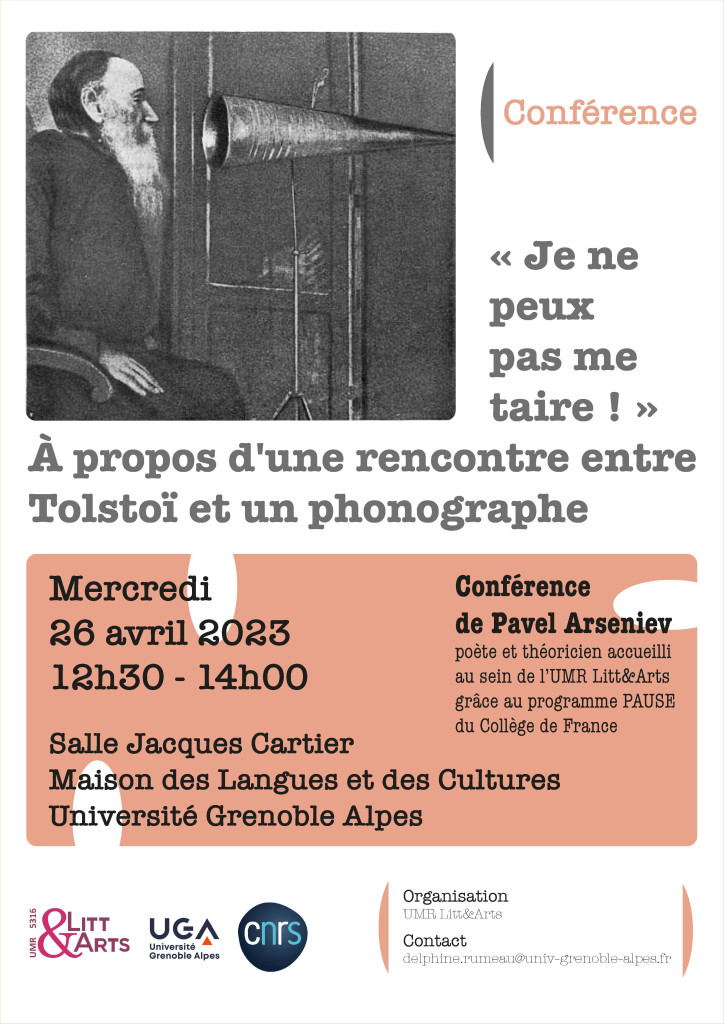

“Je ne peux pas me taire!”

“JE NE PEUX PAS ME TAIRE !”

À PROPOS D’UNE RENCONTRE ENTRE TOLSTOÏ ET UN PHONOGRAPHE

Saint-Martin-d’Hères — Domaine universitaire

Maison des Langues et des Cultures

Salle Jacques Cartier

Publication

La rencontre, qui fera l’objet d’un échange autour de la poésie, a lieu mercredi 26 avrild, au Tonneau de Diogène.

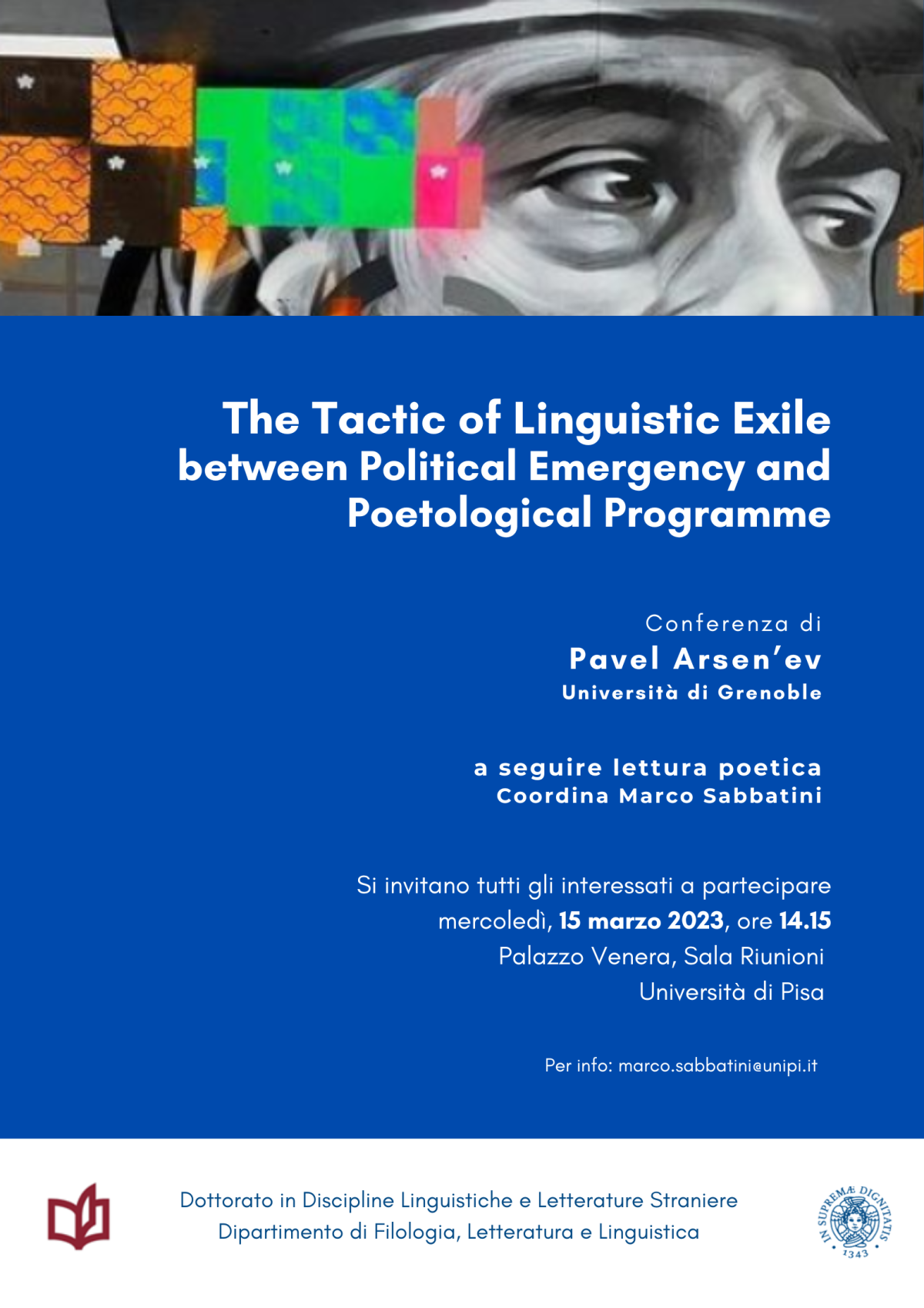

Geoposition(ing) of speech

15th March 2023, 2:15 pm, Sala Riunioni, Palazzo Venera Pavel Arsenev (Università di Grenoble)

The Tactic of Linguistic Exile between Political Emergency and Poetological Programme

The most current concept of relocation seemingly points to a purely geographical shift and thus deproblematicises political relations within the “homeland” (with which «emigration», in turn, was still very much concerned). However, what is relocated outside the door returns to the window (of our browsers) and questions about speech geoposition arise: today, it might even be more important from where you speak than what you say and where you are (although this is most often connected). This new sense of a geo-position should now be clarified by the metadata of any public/private speech: “Ah, you just (not) speak from Russia now? And what is it that you seem to be expressing not in Russia? In order not to sound too much from Russia”, etc).

The crack runs already through the very history of the language, before only non-we spoke a foreign language, now we ourselves have become half non-we, since the speech of one half of the Russian-speaking population has lost its meaning for the other half. This linguitistic division can also be seen as the appearance of a fourth East-Slavic language). So far, it might still only be a phraseological and intonational misunderstanding between Russian speakers from “here” and “there”, sometimes getting lost in this uprooted deixis. But there seemingly appear two Russian languages now, like passports — internal and external. One cannot get the second one, and someone else on the contrary has long lost the first one.

Video-recording of the event

Text of the lecture

The Tactic of Linguistic Exile between Political Emergency and Poetological Programme // Free Voices in USSR (english) / Voci Liberi in URSS (italiano)

Poésie en/d’exil (résidence)

le vendredi 18 novembre 2022, à 19h00 Avec |

|

|

En partenariat avec L’atelier des artistes en exil et Montévidéo & La Cômerie À Montévidéo, 3 imp. Montévidéo, 13006 Marseille

« Depuis que j’assiste ou même participe aux événements du Cipm et de l’Atelier des artistes en exil, j’ai inévitablement ressenti une condensation phraséologique autour de notion d’exil, qui, il s’est avéré, peut avoir sa propre poétique. Bien que cela ne rende pas politiquement la position de l’exilé plus optimiste, elle peut être comprise et habituée linguistiquement. J’ai été attiré par la notion d’exil linguistique qui a émergé ici : nous nous retrouvons tous jetés dans telle ou telle langue, y agissant d’abord par le ressenti et doutant de nos expressions (et de ce fait, dans ce qui s’y exprime aussi), mais peu à peu on s’habitue à compter cette langue native, on l’utilise presque sans réfléchir, peut-être même en perdant l’intérêt ou l’attention envers lui. La prochaine fois, nous ressentons à nouveau une anxiété langagière dans trois cas — 1) si nous avons des enfants qui l’apprennent par tâtonnement et que nous sommes assez attentifs à ce processus; 2) si nous écrivons de la poésie dans lesquels l’action des expressions courants est suspendue, le sens est redéfini, et l’adressage est dispersé ; et enfin 3) si nous nous trouvons dans un exil politique ou économique et cherchons à nous installer dans un nouveau pays, une nouvelle culture et une nouvelle langue. Pourtant, chacun de ces cas tout à fait extraordinaires nous renvoie au sens du langage, rendant son usage à nouveau incertain, attentif et intéressé. De plus, le sens de la matérialité linguistique est aggravé dans le cas de traductions poétiques mutuelles de deux exilés linguistiques — de régions aussi différentes que l’Afghanistan post-séculaire et la Russie post-soviétique, apparemment retrouvés en exil politique pour des raisons comparables, mais traitant le problème de l’exil linguistique dans des manières différentes (parmi les modes de le traiter, on peut mentionner l’essai de maintenir un lien avec la langues native en exil, de négocier avec diaspora, ou un métissage radical avec l’autre langue). Bref, ces tactiques d’exil linguistique, en partie abstraites comme programmes linguo-philosophiques, et d’autre part assez politiquement urgentes, je les proposerais comme cadre de travail sur les traductions ou y consacreraient notre éventuel dialogue avec Mustafa. » Pavel Arsenev

|

«Disparition élocutoire»

Objet poétique, en hommage à S. Mallarmé

«Je est un autre»

Objet poétique, en hommage à A. Rimbaud

«Si un poème est jeté à travers une fenêtre, il devrait se briser…»

Objet poétique, en hommage à D. Kharms

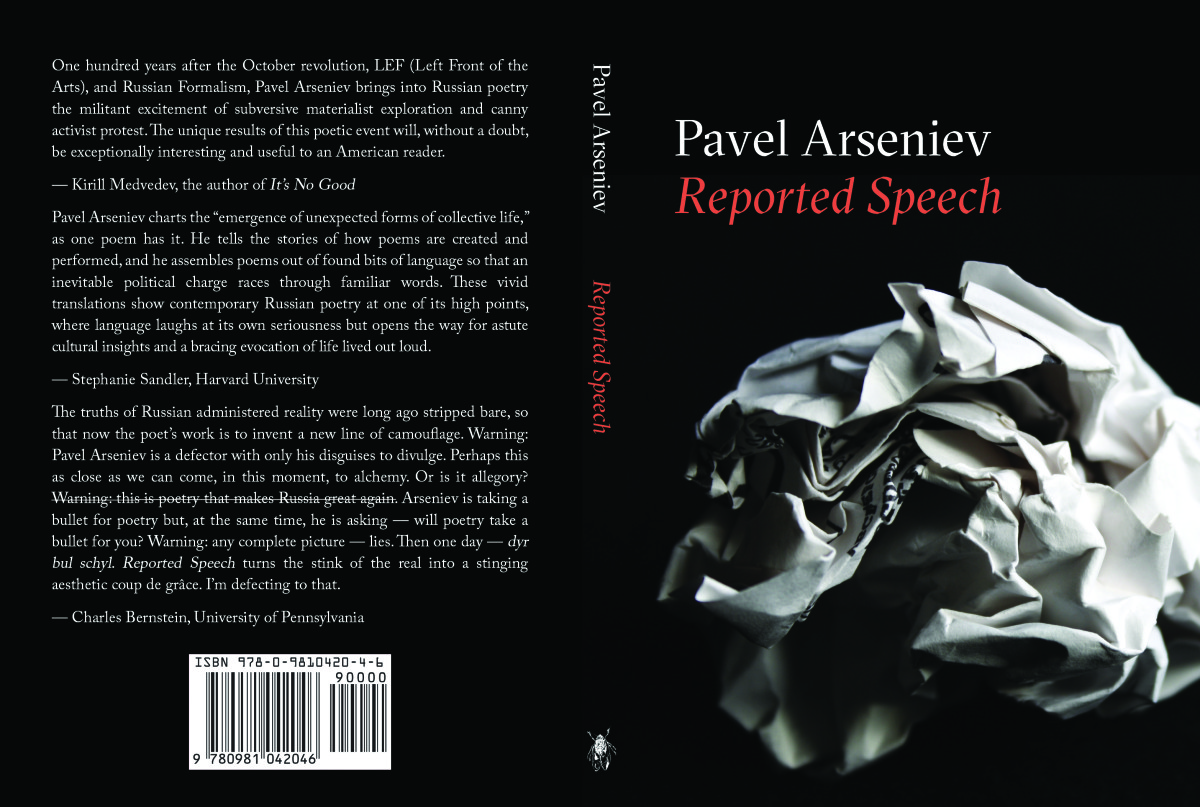

Reported Speech (NYC, 2018)

- Pavel Arseniev. Reported Speech (New York: Cicada Press, 2018)

This is the first bi-lingual English-Russian edition of Pavel Arseniev’s poetry. Arseniev is a St. Petersburg writer, editor, political activist, theoretician, and recipient of the Andrei Bely prize, Russia’s most prestigious literary award. The book contains an introduction by Kevin M.F. Platt (University of Pennsylvania) and is edited by Anastasiya Osipova.

Arseniev’s poetry provides a living link between the legacy of the 1920s Soviet avant-garde art and theory, on the one hand, and the modern Western materialist thought on the other. It traces how these diverse influences become weaponized in the language of contemporary Russian protest culture. Arseniev readily politicizes all, even the most mundane facts of the poet’s life, while at the same time, approaching reified bits of found speech and propaganda with lithe, at times corrosive irony and lyricism.

“One hundred years after the October revolution, LEF (Left Front of the Arts), and Russian Formalism, Pavel Arseniev brings into Russian poetry the militant excitement of subversive materialist exploration and canny activist protest. The unique results of this poetic event will, without a doubt, be exceptionally interesting and useful to an American reader.”

Kirill Medvedev, the author of It’s No Good

“Pavel Arseniev charts the ‘emergence of unexpected forms of collective life…’ These vivid translations show contemporary Russian poetry at one of its high points, where language laughs at its own seriousness but opens the way for astute cultural insights and a bracing evocation of life lived out loud.”

Stephanie Sandler, Harvard University

The truths of Russian administered reality were long ago stripped bare, so that now the poet’s work is to invent a new line of camouflage. Warning: Pavel Arseniev is a defector with only his disguises to divulge. Perhaps this as close as we can come, in this moment, to alchemy. Or is it allegory? Warning: this is poetry that makes Russia great again. Arseniev is taking a bullet for poetry but, at the same time, he is asking – will poetry take a bullet for you? Warning: any complete picture – lies. Then one day dyr bul schyl. Reported Speech turns the stink of the real into a stinging aesthetic coup de grace. I’m defecting to that.

Charles Bernstein, University of Pennsylvania

Reviews:

- Ambiguity and Bilingual Art: Pavel Arseniev’s Reported Speech in Review

Asymptote | February 27, 2019 | by Paul Worley

In a bilingual Russian-English format, Arseniev’s work articulates intimate, defiant, and at times desperate responses to a world in which culture seems to be increasingly prefabricated, predetermined, and designed to numb the mind and soul.

Exposing the absurd vagaries of the present moment is where the volume shines as a tremendous piece of internationalist literature.

Through art like Arseniev’s poetry, we gain a toehold, however momentary, from which we are better able to grasp the present and prepare a future.

As a keyhole into contemporary Russian experimental poetry, the volume should find a broad readership in the English speaking world. In essence, the book represents poetic strategies for resistance and survival under fierce oppression, underscoring that literature matters, as well as how it does things.

- You Cannot Even Imagine Us

Tribune | May 21, 2019 | by Giuliano Vivaldi

Pavel Arseniev’s poems of solidarity and alienation illuminate the phantasmagoria of capitalist Russia.

«By concentrating as much on the act as on the content of speech, Arseniev seems also to have come closer to documenting aspects of the very tenor of life and reality in the present epoch. Through using the genre of police reports or of legalese in ‘An Incident’ and ‘Forensic Examination’, or the language of adverts in ‘Mayakovsky for Sale’ and ‘Mass Median’, a series of brief news items in ‘Reports from the Field’, or the long parodic poem-diatribe in nationalist hate-speech In response to a ‘Provocative Exhibition of Contemporary Critical Art’, we discover not the poet’s perspective, but a concrete, material trace taken from excessive speech which illuminates the strange capitalist phantasmagoric world that is contemporary Russia.»

- Polyphonic Transpositions: Pavel Arseniev’s “Reported Speech”

Reading in translation | June 21, 2019 | by Molly Thomasy Blasing

From its very first pages, Pavel Arseniev’s Reported Speechshows itself to be true to its title; the opening poem’s epigraph comes to us, we are told, from an “Instruction in the platzkart train car”. This is only the beginning of a journey through a trail of words found, mixed and transmitted from various source texts. The poems represent “reported speech” in the sense that they are inspired by found texts, by language encountered on the streets, in police stations, rail cars, courtrooms, newspapers, books, personal correspondence, nationalist political screeds, and writing on social media and the internet. The poet appropriates, organizes, shuffles and shapes the material of the political world, which is everywhere, for everything is political.Pavel Arseniev is part of a group of contemporary Leftist poets developing new modes of resistance and protest through literary production. Arseniev’s unabashedly political project rejects any view of art and art institutions as motivated by a search for the next singular voice of creative genius. Rather, his creative practice seeks to dismantle the idea of poetry as narcissistic, individualistic self-expression and instead aims to capture and convey aspects of human social experience in the world through the multifaceted voices of the collective.

His larger creative project is to facilitate the dissemination of socially engaged and marginalized speech and, in some ways, to continue the legacy of the Russian avant garde and factographic movements of the 1920s. Arseniev also sees his mission in part as working to fill a void left in the wake of the collapse of samizdatculture of the 1970s.

- Book Reviews in Slavic Review #79 (2020)

by Michael Lavery (UCLA)

If Amelin mounts a defense of poetry against the threat of modernity by digging

into the roots of tradition, Pavel Arseniev, in contrast, questions why it needs defending in the first place. In Arseniev’s view, the formal and institutional constraints of Russian verse have rendered it useless in articulating the present moment. His is an engagé poetry that articulates a leftist critique of the myriad forms of social and political alienation in contemporary Russia. The translations found in Reported Speech, executed by a collective of translators overseen by editor Anastasiya Osipova, effectively recreate the urgency and relevance of his project.

In both his poetry and his political activism, Arseniev attempts to overcome the

futility of traditional methods of resistance. Civic verse and revolutionary discourse are no longer as meaningful as they once were, having been co-opted and commodified by state and commercial interests. Arseniev’s answer is to subvert the role of the poet by acting as a field reporter, providing snapshots and snippets of speech from everyday life. In “Mayakovsky for Sale” (24–25), a list of hyperlinks from an online advertisement for a used volume of the poet’s collected works becomes a statement on the market’s power to subsume everything into its domain. Another poem, “Translator’s Note” (38–43), consists of lines excerpted from a Russian translation of a philosophical tract by Ludwig Wittgenstein. In their transformed context, these disconnected scraps take on new meanings, challenging the reader to reconsider traditional notions of authorship and originality.

Arseniev’s innovations are informed by his concerns about the viability of political poetry. Perhaps a poet in Russia should be less than a poet after all. At times he anticipates critiques of his approach by assuming the voices of his detractors, as in “Forensic Examination,” which reads like a report by a state prosecutor indicting the poet with inciting political extremism:

We shall see the writer

Has attempted

To voice his political

Views and convictions,

Clumsily camouflaging them

In aesthetic window dressing.

Its objective qualities,

According to many experts,

Are surely

Much poorer

Than if he had minded his own business

And simply written poems,

Looking for his own style

And his own place on the literary scene (45).

A similar satirical wit appears in “Poema Americanum,” in which a visit to a

west coast university prompts the poet to reflect on his own marginality: “in time you will stop being a person / whose acquaintance is sought out by the slavic studies professors / wishing to appear more radical” (133). In this poem, as throughout the entire volume, the translation deftly captures the contrasts between a multitude of voices and perspectives, allowing Arseniev’s multifaceted authorial presence to appear starkly on the page.

27 November Pennsylvania University | Readings & discussion @K.PLatt’s seminar

29 November City University of New York (Hunter College) | Poetry Reading and Book Talk

30 Novembre — 1 December Yale University | Symposium «Pointed Words: Poetry and Politics in the Global Present»

2 December New York City | Readings @Ugly Duckling Press Headquarters

4 December Chicago University | Readings & discussion @R.Bird’s seminar

5 December Harvard University | Readings & discussion @S.Sandler’s seminar

8 December Boston | Readings @ASEEES

12 December New York University (Jordan Center) | Poetry Reading and Book Talk @Jordan Center

25 мая Москва | Библиотека им. Н.А. Некрасова

29 июня Санкт-Петербург | Новая сцена Александринского театра

Записи чтений и дискуссий

Серия лекций-перформансов «Как научиться не писать стихи» (Гиссен, Москва, Самара, 2019-2020)

Презентация книги «Reported speech» на Новой сцене Александринки при участии Кевина Ф. Платта, Джейсона Сипли, Анастасии Осиповой (Петербург, 2019)

Презентация книги «Reported speech» в Некрасовке при участии Игоря Гулина, Бориса Клюшникова, Никиты Сунгатова (Москва, 2019)

Presentation of «Reported Speech» (U.S., 2018)

- Poetry Reading & Book talk @ New York University (Jordan Center)

- Readings with Polina Barskova, Eugene Ostashevsky, Matvei Yankelevich & Others @ASEEES

- Readings & Discussion @ Harvard University (Stephanie Sandler’s seminar)

- Readings & Discussion with Kirill Medvedev @ Chicago University

- Readings @ Ugly Duckling Press Headquarters (New York City)

- Readings & Roundtables @ Yale University (Symposium «Pointed Words: Poetry And Politics In The Global Present»

- Poetry Reading & Book talk @ City University Of New York (Hunter College)

- Readings & Discussion @ Pennsylvania University

…

Чтения в рамках конференции «Dmitri Prigov, Adresse aux Citoyens» в Pompidu Centre (Париж, 2017)

Readings with Charles Penequin at New Stage of Alexandrinsky Theater (2016)

Выступление на фестивале современной поэзии Audiatur (Норвегия, Берген, 2016), перевод на английский читает Joshua Clover

Вечер возвышенных стихов на Приговских чтениях (2016), начиная с 11:37

Чтения на церемонии вручения Премии им. Драгомощенко (2015), начиная с 36:36

Чтения в ДК Розы (Введенский, Зукофски и собственные тексты)

Чтения на вечере «Дистанции» (совместно с И. Гулиным, Н. Новгород, 2015)

Чтения в галерее Artspace New Haven (совместно с А. Скиданом и К. Чухров, 2015)

Чтения на церемонии вручения Премии им. Драгомощенко (2014), начиная с 34:06

Чтения в Берлине (совместно с К. Корчагиным, 2014)

Чтения на коллоквиуме «Поэзия и философия» (2013)

Чтения на #ОккупайАбай (совместно с Р. Осминкиным и К. Медведевым, май 2012)

Чтения на презентации крафт-книги «Бесцветные зеленые идеи яростно спят» (10 декабря, 2011 года)

Чтения на вечере «Новая кровь в «Старой Вене» (совместно с Д. Гатиной и Р. Осминкиным, 2011)

Чтения в рамках программы “Контекст” (2009)

Дискуссия по выставке Павла Арсеньева «Орфография сохранена» (14 мая 2012 года).

Модератор дискуссии Елена Яичникова. Участники дискуссии: Глеб Напреенко, искусствовед, арт-критик Олег Аронсон, философ, теоретик кино и телевидения Павел Арсеньев, поэт, художник. Иван Ахметьев, поэт, критик, редактор. Данила Давыдов, поэт, прозаик, литературный критик.

Выступление на TEDxNevaRiver об Уличном Университете (2012)

Доклад «Новые медиа и новые формы гражданской демобилизации» в галерее StellaArt Foundation (2012)

Доклад об идеологии книжной серии *kraft на открытии Центра Андрея Белого (2012)

Доклад “Текстовые интервенции в городской среде” в школе «Что делать» (2012)

Слово лауреата при вручении Премии Андрея Белого (2012)

Доклад «Прагматическое измерение поэтического высказывания» (теоретический блок «Самообращенность высказывания в актуальной поэзии и современном искусстве», 2014)

Дискуссия «Вестернизация русской литературы» (совместно с А. Секацким и Э. Шелгановым, 2014)

Слово номинатора на Премии Драгомощенко (2015)

Коллоквиум «Исчезающие языки» (2015)

Речь о Полине Барсковой на церемонии вручения Премии Андрея Белого (2015)

Artist-talk «On [Translit], magazine and community» at Audiatur Poetry Festival (Bergen, 2016)

Artist-talk «On documentary poetical objects» at Audiatur Poetry Festival (Bergen, 2016)

Лекция-перформанс «Вынос мозга: поэзия между мнемотехникой прошлого и искусством стирания будущего» на 101. Mediapoetry festival: Форматирование памяти (2016)

Lecture and discussian (in dialog with Chiara Figone) at «Libraries of the Future» at Centre Pompidou (2016)

Artist-talk «The sign with double agency: self-consciousness of a transparent actor» at Tokamak-residency (Helsinki, 2016)

Доклад «Рождение методологической пластики из духа производственной травмы и мобильных интерфейсов» на коллоквиуме «Знание на экране: новые режимы видимости в социогуманитаристике» (2016)

Доклад «“Бросок костей” между жестом и шифром» на семинаре по прагматической поэтике (2016)

Выступление «О реляционной онтологии литературы в рамках крауд-кампании #19 [Транслит] (2016)

Речь о Pastiche project на церемонии вручения Премии Андрея Белого (2016)

Мини-курс лекций по прагматической поэтике (2017):

- «Коллапс руки: производственная травма письма и инструментальная метафора метода»

- «От камня к молотку: от инструментальной метафоры письма и феноменологии литературного труда»

- «Паровоз, автомобиль и другие двигатели литературной эволюции».

- «Штыки, перья и другие машины войны»

Доклады «Исчерпаемые и неисчерпаемые художественные ископаемые: камень Шкловского и камень Хармана» и «То, что никто никогда не видел»: большие данные против корреляционизма в литературоведении на коллоквиуме «Объектно-ориентированная поэзия» в галерее Anna Nova (2017)

Artist-talk «Documentary-Poetic Objects How to Plug the Poetic Subject into the Material in the Post-Lyrical Age» at Stanford University (2017)

Дискуссия «Перманентная революция и арт-пролетариат» (совместно с А. Секацким, А Лоскутовым, Л. Данилкиным и др.) на международном форуме «Искусство прямого действия» в Музее стритарта (2017)

Доклад «Vous n’avez encore rien vu»: к прагматике акселерации образа/письма» в рамках коллоквиума «Критика спектакля»: ритмы переломного времени и вопрос о статусе изображения в искусстве (2017)

Выступление «Политика дейксиса» в рамках «Открытого университета» (2017)

Речь об Илье Будрайтскисе на церемонии вручения Премии Андрея Белого (2017), начиная с 39:30

Дискуссия «Воображение и факт» в Электротеатре (в рамках фестиваля «Третьяков.doc»), которая в первый день была посвящена кинолистовкам, а также фильмам Криса Маркера и группы «Медведкин» (совместно с Н. Изволовым и Н. Смолянской), а во второй — кинолистовкам и фильму группы «Дзига Вертов» (совместно с теми же и К. Адибековым)

Выступление в рамках «Ночи идей» («Idées de la nuit») Французского института (2018)

Лекция «Некий двигающийся зрительный аппарат: чтение машинным способом» (2018)

«Би(бли)ография вещи» или литература на поперечном сечении социотехнического конвейера (2018) / Лекция, прочитанная в рамках публичной программы выставки «Генеральная репетиция»

…

«От зауми до Нового ЛЕФа: что читать о революции в языке» / лекция в Музее-библиотеке Н.Ф. Федорова (2019)

«Могут ли факты говорить за себя?» / Лекция в ДК Розы (2019)

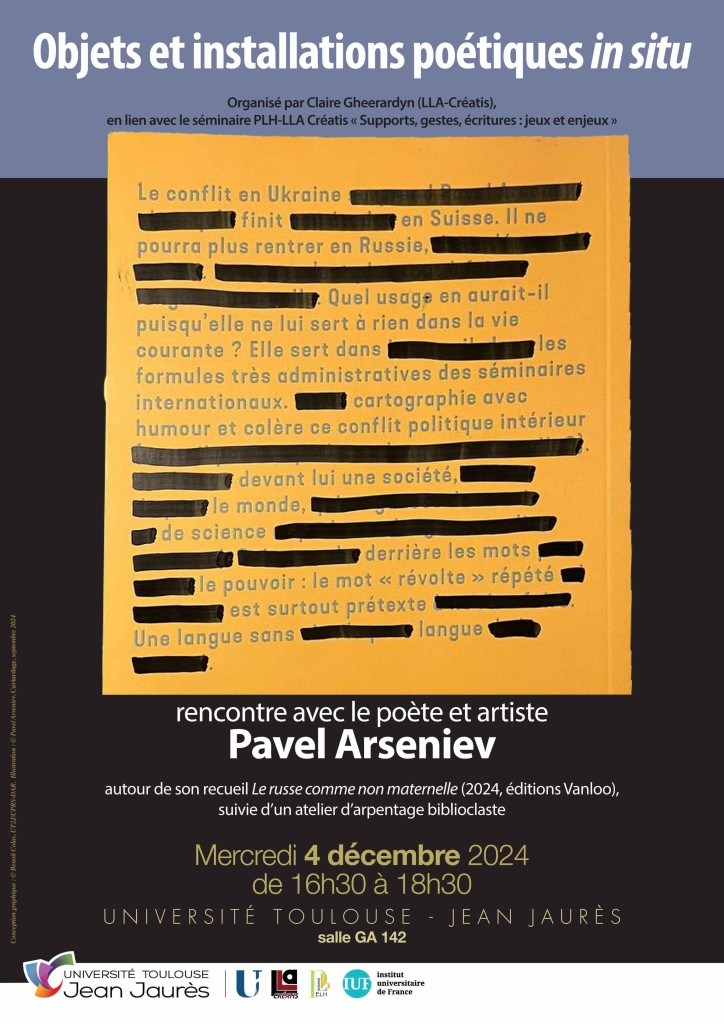

4 décembre,

4 décembre,